Image: iStock

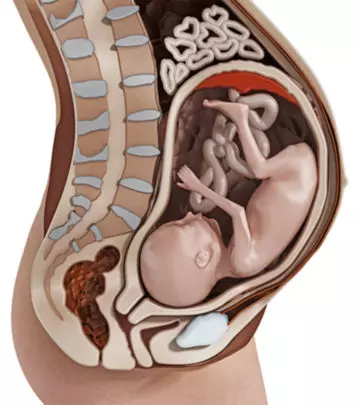

Women have the gift of creating and growing a life inside them. While pregnancy and childbirth might sound like nature’s marvel, it is interesting to understand how your body works at the end of pregnancy and during childbirth. Knowing what happens to your body at the time of childbirth might also prepare you better for labor and birth.

Understanding the anatomy

Firstly you will need to understand the anatomy of the structures around your baby while in the womb:

- Your pelvic bones and muscles provide support to the growing uterus and your baby. They also form the passage for your baby during birth.

- The uterus surrounds the baby and keeps growing as the baby grows.

- The cervix is the neck of the uterus, composed of a different tissue.

- The cervix is thick and closed during pregnancy. As you near the time of birth, the contractions make the cervix draw up into the body of the uterus. The cervix then gets thinner, and the process is called effacement. The opening of the cervix is called dilation. When it is fully dilated, which is about ten centimeters, the contractions help the baby pass from the uterus into the vagina.

- The cervix is lead to the outside of the body through the vagina. The inside of the vagina has many folds called rugae.

Here’s what happens in your body before labor begins

- In the last few weeks of pregnancy, your body begins to prepare for childbirth. Here are the primary changes that begin to take place.

- Your hormones begin to soften the ligaments between the bones and pelvis. It provides your pelvis more room for birthing. You could sense a shift of balance this time around. Your joints may also feel looser, and you could have a sore body.

- Other hormones begin to work on softening your cervix, which is closed for the most part of the pregnancy while holding your baby in the uterus. The opening of the cervix constitutes most of the work in labor. The cervix remains closed in some women until they go into labor. But in a few women contractions starting before the labor could dilate the cervix by three or four centimeters before the onset of labor. Your doctor might check your cervix at your prenatal appointments especially when the due date approaches. However, it does not make the sole predictor of when you are going to be in labor.

- Your baby starts to move lower in the pelvis. The process is called engagement. If your body feels an increasing pressure in your lower abdomen or if you feel that your breathing has become more relaxed, then your baby has started moving down. If it happens a few weeks before birth, it is fairly visible, and your peers might begin to say that your “baby has dropped”. It takes place a few weeks before birth in first-time mothers. For second or third time mothers, it’s not until the labor begins that the engagement occurs.

- You might experience blood-tinged mucous called the ‘mucous plug’ which had been inside the cervix during your pregnancy. The mucous plug would loosen as the cervix begins to soften and open and it would begin to pass from the vagina. There might be an increase in the mucous passage for few weeks or days before labor begins in a few women, while some women might not notice the plug at all.

- The breaking of waters might happen before the onset of labor. Usually, contractions will follow within a day after your waters have broken. You should see your doctor at once.

- Pre-labor contractions might happen with any of the symptoms mentioned above. Most women might not take note of pre-labor contractions until the labor starts intensely. But some women might experience them as a painful event that could disrupt their sleep or other activities.

- Braxton-Hicks contractions are false contractions that could be irregular and not necessarily painful. They would subside with a changing activity or might occur more often. You may experience these contractions for several hours before they stop or you might have them for several days at irregular frequencies.

The Stages Of Labor

- The first state is Dilation, whereby the contractions open your cervix.

- The second stage is Pushing, wherein you push the baby into the vagina and out into the world.

- The third stage is Placenta, whereby the contractions would continue so you can push the placenta out.

1. The Dilation Stage:

The dilation stage involves the hormones working on softening and opening the cervix with the contractions getting stronger and more regular. The contractions of the uterine muscles pull the cervix up and put pressure on the baby giving it a downward movement. The pressure of the baby’s head against the cervix during contractions also contributes to thinning out and opening the cervix. The dilation stage is further divided into early labor and active labor phases.

During early labor, the contractions are stronger and less apart. Early labor is when slow dilation and effacement occur. The early labor phase varies in duration and is difficult to predict as in some women it might pass quickly, but some might have to experience it for more than a day.

The active labor phase is when the contractions are strong and regular with a frequency of three to five minutes. The cervix changes more quickly. One can predict the duration of active labor. First-time mothers have an active labor anywhere between five and ten hours while subsequent-time mothers might have anywhere between two and eight hours of active labor.

2. The Pushing Stage:

You will have the urge to push once the cervix is fully opened and the baby has descended low into the pelvis, pressing on the pelvic nerves and muscles. Some women feel like pushing the baby even before the cervix is fully dilated.

When you feel the involuntary push from the uterus, then push gently. You might not be able to stop the uterus, but you could avoid holding your breath. If the cervix is fully open but you don’t feel like pushing, you might want to wait until the baby is lower and get the urge to push.

Moreover, you might feel the downward movement of your baby who has been making some turns as it travels through the pelvis to make the best fit. An intrathecal anesthesia or epidural would make you feel strong pressure during the second stage, which helps you figure out when to push. Women who take epidural might have longer labor than women who don’t take the epidural.

3. The Third Stage:

Your baby arrives into the world. Your placenta is ready to come out, and you will be asked to push out your placenta. Your uterus keeps doing its job as it contracts and reduces in size so that the placenta detaches from the source. After this, you need only a few pushes to evict the placenta.

You should be able to push out the placenta within a few minutes after birth, but a delay of up to 30 minutes is considered normal. Alternatively breastfeeding your baby or stimulating nipples can trigger contractions.

Oxytocin is what you need to trigger the placenta separation. So if it doesn’t happen naturally, then doctors might give you oxytocin or a medication that pushes out the placenta while minimizing the bleeding.